Some say heroes are people who are brave for just five minutes longer. For Ian Villatoro, it was 36 hours.

The first hour began around 6 p.m. on January 8, 2025. Wildfires were sweeping through the Los Angeles metropolitan area, and Villatoro was at home in North Hollywood, watching the news. “It was really scary,” recalls Villatoro. “A fire was spreading in Hollywood Hills, and a lot of people don’t have cars there.”

Villatoro knows this partly because he’s lived in L.A. his whole life and partly because of his occupation. Villatoro drives with Lyft part-time — a compromise with his wife after he splurged on a Model Y Tesla. “Plus, I like company on my commute.”

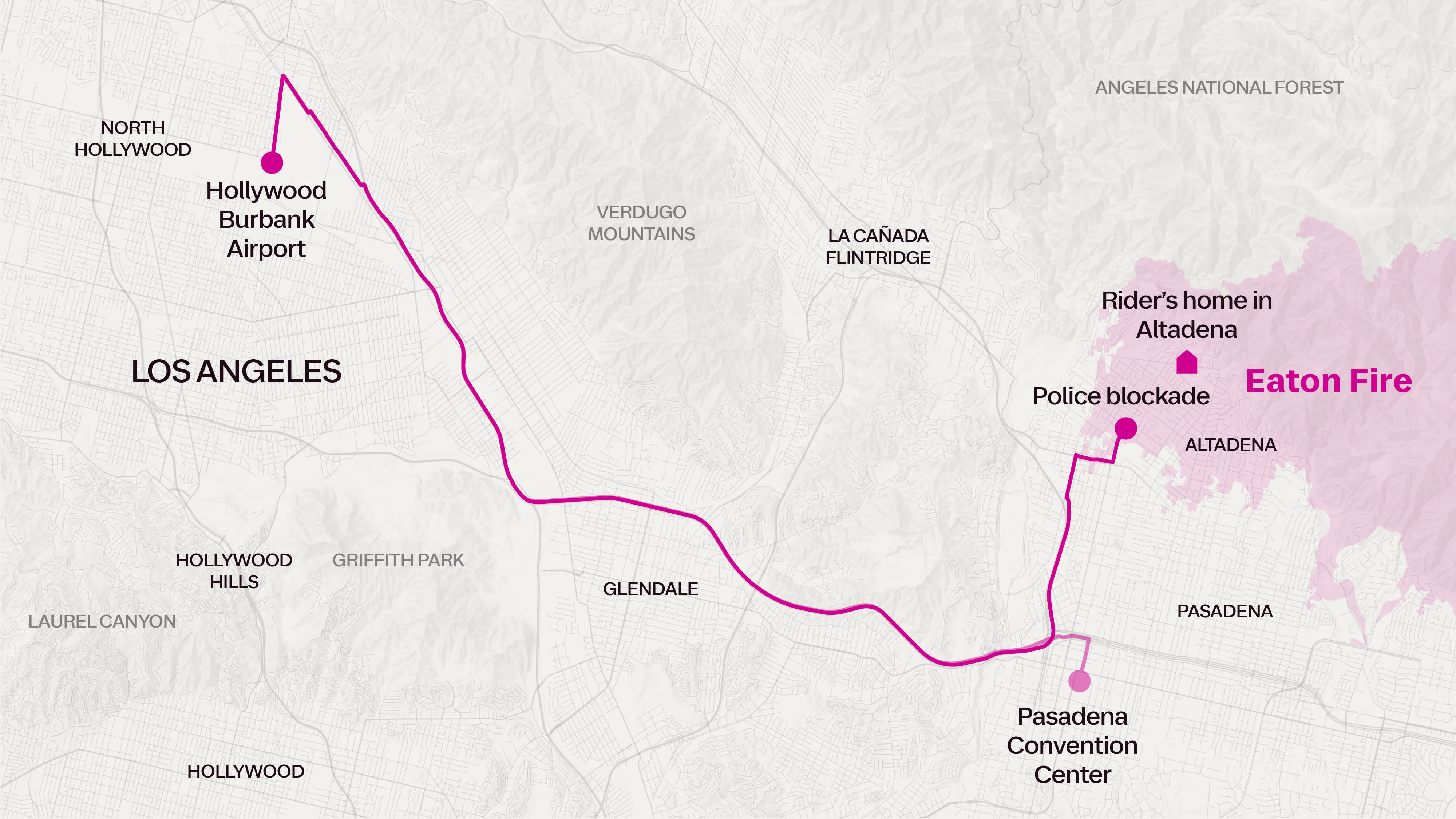

In that moment of crisis, Lyft also became a way to serve his city. “Everyone was like, ‘How can I help?’ ” recalled Villatoro. “I realized I could.” He turned on the Lyft app. As expected, his first ride took a rider out of the Hollywood Hills to the Burbank airport.

At the airport, he took another request and immediately noticed that his new rider seemed very tense. Villatoro pressed on with some small talk, asking where the rider was visiting from (Oregon, but his father lives in L.A.). It was only after Villatoro asked where the rider’s father lived — Altadena — that Villatoro understood what was going on. The neighborhood was in the thick of the fires, and their destination was the Pasadena Convention Center, the evacuation location for those who had escaped.

As the rider shared more, Villatoro grew more worried. The rider’s father was elderly and lived alone, he didn’t use technology, and his neighbors were out traveling; there had not been any contact with him for almost two days. Villatoro had lost his own mother a year earlier and remembered feeling the desperate urgency to make sure she was OK after she’d had a heart attack. He had jumped on a plane the minute he found out, just like his rider. Villatoro knew that the rider needed to find his dad, but without a car and community in L.A., it would be challenging.

Villatoro, going above and beyond the call of duty, proposed they try to get to the rider’s father’s house instead. The rider agreed, and the pair re-routed to Altadena — directly in the middle of the fire zone.

They made it about three miles from the house before being stopped altogether by police officers. There was chaos and fires everywhere. No one knew which homes might still be standing.

By then, it was around 10:30 p.m., so Villatoro and the rider resigned to head to the convention center. Throughout the hours of searching, they had become friends, and Villatoro understood his personality more clearly. Before dropping off the rider, Villatoro said: “Take my number. And call me if you need any transportation.”

Villatoro could hardly sleep that night. Instead, he did research, pulling up the father’s house on Google Maps and planning out different routes to get there. Zooming in on one Street View image, Villatoro found he could make out the father, loading something into a car. That made everything feel more real — and urgent.

Villatoro did all this research without even knowing whether the son would reach out. At 6:30 a.m., Villatoro called him. The rider had looked through every bed in the evacuation center and called every single hospital. No trace of his father.

Villatoro offered to drive him to the house. When the rider agreed, Villatoro and his wife — who had promptly cleared her calendar for the day — went to pick up the rider, this time in their SUV. “I didn’t know what the terrain was going to be,” he says.

As they followed the route that Villatoro had studied, the sense of urgency was palpable. “It was very much still an active fire,” recalled Villatoro. “Think of a very thick fog, but it was smoke. Even the officers manning the barricades weren’t outside; they were in their vehicles.” After trying several different routes to get as close as possible — all unsuccessful — they came across a blocked side street about two miles from the house.

Before Villatoro could even finish asking if the rider was comfortable walking, he was out of the car. So together, the three of them headed out. Because there was no reception (cell towers were damaged), they relied on screenshots of Villatoro’s map to guide them.

“It was apocalyptic,” recalls Villatoro. Some houses still had active fires, and flames were shooting out of the gas meters. Others were reduced to rubble and shards. Whole neighborhoods were just flattened. And yet, here and there, they would come across one house that was completely untouched. “That gave us hope,” Villatoro says. “Everything the rider had told us about his father — a resilient and stubborn old man who refused to move to an assisted living home… We all hoped his house would be the miracle still standing.”

Plucking their way over downed power lines, they finally turned onto the street that led to the house. “When I looked up, I couldn’t see anything,” Villatoro recalled. All the hope that had motivated them for the past three hours vanished. “Everything was rubble,” he says. “The one thing that was standing was a five-foot metal file cabinet.” Leaving the rider in the middle of the street, Villatoro made his way over — and eventually caught sight of something that was unmistakably the rider’s father’s remains.

Villatoro’s wife saw him pause. She had been taking a video, in which you can see her hand slip and hear a cry come. As Villatoro turned back, he shook his head and went over to hug him. “He cried, just hysterically. All I could say was, ‘I’m so sorry.’ ”

As Villatoro and his wife consoled the rider, there was also a kind of relief. The rider had not slept for 36 hours since hopping on a plane from Portland to search for his father. If they hadn’t gone looking for themselves, the rider might not have known for weeks — there was so much destruction for police to sort through.

And there was a secondary relief that Villatoro and his wife had been there to help the rider process, make decisions, and protect him from the worst of it. As Villatoro reflects, “I was happy to be the one that spotted him, because otherwise that would have been devastating. Imagine that being the last image of your father.”

Walking back down, Villatoro was able to flag a police car and organize a way to preserve the father’s remains. Later, lingering over half-eaten meals, the rider expressed his gratitude to Villatoro and his wife. “It’s closure,” reflects Villatoro, despite the terrible outcome.

A full 30 hours after he had picked the rider up from the airport, Villatoro dropped the rider off at his hotel — he was flying back the next day. But they stayed in touch. Two months later, Villatoro and his wife attended the service for the rider’s dad.

Looking back, Villatoro feels very grateful he was there at the right place at the right time. But he was also the right guy. “I’m the go-to guy in my family when there’s a crisis,” Villatoro says. “I like to be able to do that for others.”

Villatoro’s story points to an overarching truth: Caring for others can make a huge difference. And perhaps, most importantly, heroes are made every day, in small ways and large, when people go out of their way to help.