Olatunji Oboi Reed was depressed. A 48-year-old Chicago native, Reed, who generally goes by the name Oboi (pronounced “oh-by-ee”), had moved from a career in the nonprofit sector to a series of corporate positions with companies like J.P. Morgan and Nike (where he was regional manager for Corporate Responsibility and Community Affairs). Those experiences taught him many useful skills — process, leadership, project management. “It also taught me,” he says, “that it may not be the right environment for me.” He was feeling isolated and questioning, he says, “whether all this was worth it.”

And then he remembered his bicycle. It had once been his daily mode of transport, but these days it mostly stayed in his basement. “I just decided to go for a ride,” he says. “And that ride, on that beautiful Saturday morning, changed everything.”

Reed says he “immediately recognized the impact of cycling on my own mental health.” There was the endorphin rush of the exercise. There, too, was the sensation of being in nature, riding along Lake Michigan. And there was, he says, “something I’d never really considered before” — the social aspect of cycling. “I’m riding on the trail, and people are passing me with a nod or saying, ‘How you doing?’ ”

But Reed also noticed a few other things. For instance, he had to drive his bike to the lakeshore. Chicago was hardly conducive to cycling at that point, particularly on the city’s ethnically diverse South and West Sides. “I thought people who rode bikes on the street were crazy,” he says, laughing. Reed, who is Black, also noticed that he didn’t see a lot of cyclists who looked like him.

“We want people to recognize the beauty that exists in our neighborhoods.”

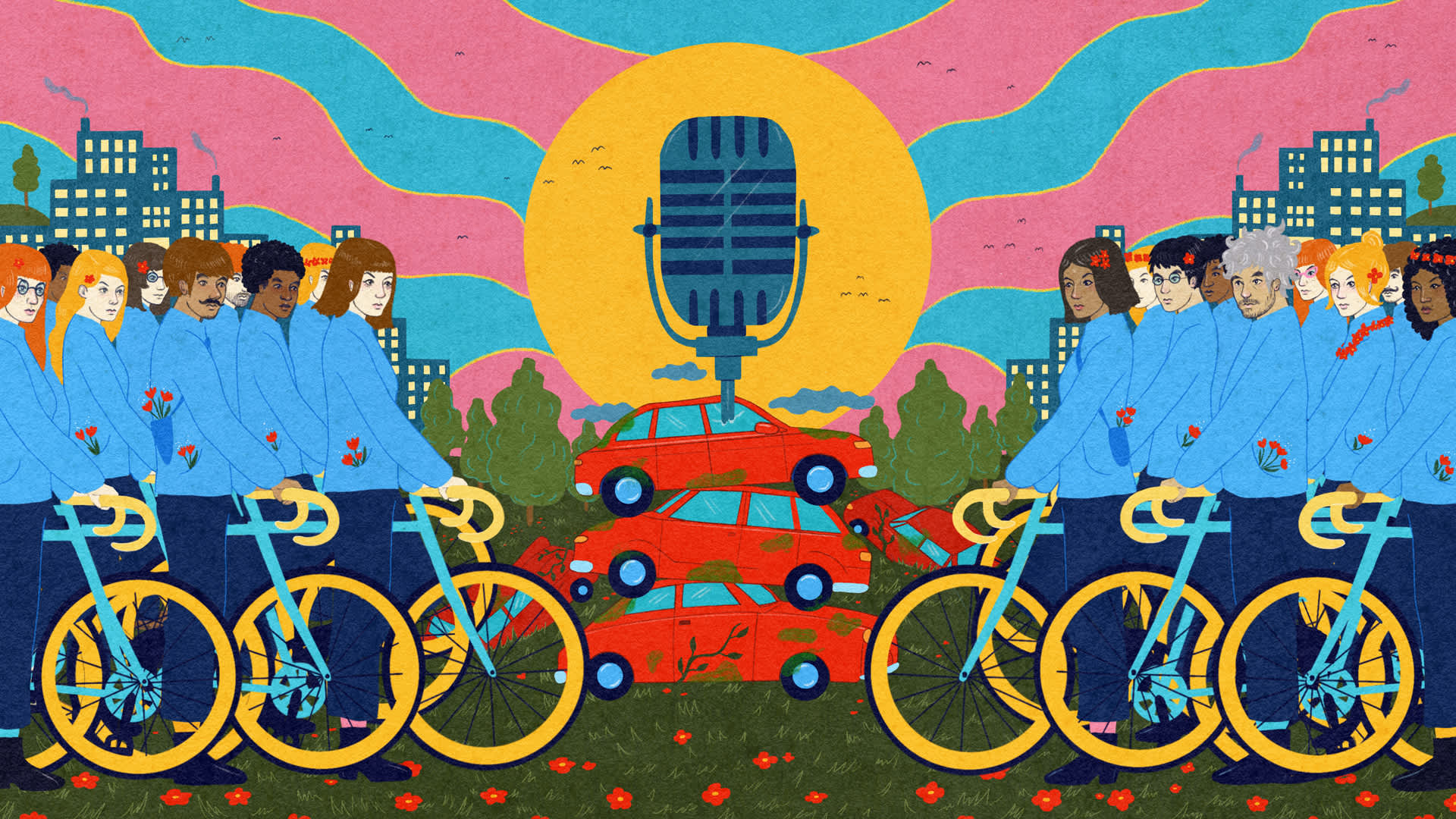

Those revelations — the positive power of cycling and the obstacles that prevent more people, particularly from communities of color, from experiencing it — would shape the next chapter of his life. Reed organized a succession of bicycle clubs, with names like “The Pioneers Bike Club” and “Red, Bike and Green,” oriented around a simple premise: “Getting Black folks riding.” In 2014, he helped found a Chicago chapter of Slow Roll Detroit, the sprawling, festive weekly bike ride that was drawing thousands of riders of all stripes on a two-wheeled parade through the Motor City (and received that ultimate encomium of cultural cachet, an appearance in an Apple ad). Slow Roll Chicago incorporated “narrators” who would highlight important locations within the community — a local shop that had been in the same family for decades, or an anti-violence mural, or an underused park — sometimes accompanied by social commentary.

“We want people to recognize the beauty which exists in our neighborhoods,” he says, as well as “to understand the inequities that exist in our neighborhoods — from inadequate infrastructure to lack of affordable housing to underperforming schools to violence.”

Slow Roll drew to a close after a few heady years, but Reed has continued the rides under the banner of Equiticity, a nonprofit he founded in 2017 to focus on how mobility — or lack thereof — contributes to racial and economic inequality, and how to marshall transportation resources to address historical harms. (Equiticity receives financial support from Lyft, among other organizations.)

Equiticity leverages the bicycle as an agent of community building and social change. One recent initiative, “Mobility Opportunities Fund,” grants stipends to residents of the largely Black Chicago neighborhood of North Lawndale to help purchase “climate-friendly modes of transportation” — bikes, e-bikes, or electric vehicles. “BikeForce,” a vocational training program at a Chicago high school, teaches students how to build and repair e-bikes, giving them expertise in a growing technology. Not all of Equiticity’s projects are focused on Chicago — a recent project helps distribute bikes in Palenque, a neighborhood of Cartagena, Colombia, that, as Reed notes, “was the first free Black town in the Americas,” settled by former slaves.

For all its promise, cycling also presents a case study of the problems Reed is trying to combat. A study by University of California researcher Jesus Barajas, which Reed helped conceptualize, found that cyclists were eight times more likely to be ticketed — for infractions like riding on the sidewalk — in majority Black neighborhoods than white ones. But those cyclists, Reed says, are typically riding on the sidewalk for fear of riding in the street. “Where we are being stopped,” Reed says, “is largely on arterial streets with no bike infrastructure.” It’s a case of what he calls “compounding inequities”: inequities in transportation infrastructure leading to inequities in enforcement.

Those inequities create unique complications. A study in Los Angeles, for example, found that shifting from driving to cycling led to a measurable reduction in mortality — but less so in Black and Hispanic communities, thanks to increased crash risk and higher exposure to pollutants. Advocates for Vision Zero — the global campaign to reduce traffic deaths and injuries — routinely call for more police enforcement; Reed would like to see low-level traffic stops, which disproportionately target drivers of color, done away with entirely. And in a series of focus groups conducted by Equiticity in Chicago, many Black and Hispanic respondents said they relied on cars not only because they felt unsafe on area streets but also because they found public transportation “exhausting,” since they felt “racialized” by other transit riders.

Any policy that doesn’t take these dynamics into account, Reed says, is destined to fail. “Try to go into one of our neighborhoods and convince somebody they should ride their bike to work — you’re going to get laughed out of the neighborhood,” Reed says. “They’re trying to get their kids to school without getting shot. They’re trying to make sure they’re not late to work because when they’re late, they get fired.” (It should be noted that studies show that Black workers have much longer average commutes than white workers.)

Equiticity designs programs with these populations in mind. For example, Reed is working with Pacoima Beautiful, a nonprofit in the diverse Los Angeles neighborhood, on what Reed calls an “e-bike library” — called Electro-Bici — comprised of a fleet of decommissioned e-bikes from the start-up Jump. Unlike the traditional model of short-term rentals, Reed says, with the Electro-Bici model, bikes can be loaned for a month, even a year. “For people in our neighborhoods, we need time to explore how bikes fit into our lifestyles,” he says.

It seems too naive to suggest that bikes alone can change the world. “The problems are systemic,” Reed says, “and the solutions must be systemic.” But a bike, as Reed knows, can change a life, kicking off a journey that’s about far more than getting from point to point.

The content provided in this article is for informational purposes only. Unless otherwise stated, Lyft is not affiliated with any businesses or organizations mentioned in the article.