Every day, millions of drivers and riders use Lyft’s app. Most of the time, they’re staring at a map — to see how long their ride will take, or to see how far away their driver is, or to get directions to their destination. And yet, until very recently, Lyft had limited control over that navigation experience, which was built using Google Maps.

“For our entire existence, we couldn’t fundamentally change that product,” says director of project management Ben Schrom. “As a product team, it’s a pretty weird experience to not own 80% of the pixels that your users interact with.”

This was more than just an annoyance. Over the years, Lyft had collected a list of hundreds of features that might improve the rider or driver experience, but it was powerless to implement them. What’s more, relying on third-party technology was creating an expensive disconnect. Lyft used its own algorithms to predict the time and cost of a ride — informing the price and ETA that a passenger sees when they order it, or that the driver sees when they accept it. But once the ride was accepted, Google took over the navigation, and sometimes its routes differed from the ones that Lyft had calculated, resulting in more expensive rides that Lyft would have to pay for. (For instance, Google always presents drivers with the fastest route, regardless of tolls. But sometimes, paying a toll would shave only a minute or two off the ride, while adding significantly to the cost.)

In 2019, a group of Lyft engineers determined that if the company suggested navigation routes, it could result in significant savings. And that wasn’t including the money it would save by not paying Google, or the potential upside from creating a safer rideshare experience. Altogether, home-grown maps could save Lyft a potentially massive amount when multiplied by the millions of rides that take place across the platform every day.

For most of Lyft’s history, there wasn’t much to be done about it. Google and Apple had spent billions of dollars and many years building their maps. It would have been prohibitively expensive for a relatively small company like Lyft to duplicate that effort. But a few years ago, Lyft found a way forward, launching a scrappy effort to build its own maps. Last year, it began rolling them out across the country. Today, they power 70% of all rides on the Lyft platform.

The breakthrough

The breakthrough came in 2019 when the team determined that the OpenStreetMap (OSM) platform was finally robust enough to undergird Lyft’s maps. Created in 2004 by a British academic, OSM is a free, open-source alternative to Google and Apple Maps — a sort of Wikipedia for maps, with volunteers contributing geographic information into a centralized database, which can then be accessed by anyone for free. OSM was mostly the domain of academics and hobbyists until 2012 when Google announced it would start charging more businesses for using Google Maps. Since then, companies from Amazon to Meta to Snapchat have built mapping products on OSM — and, in turn, contributed massive amounts of information to the underlying database.

“The only reason this worked was because OSM’s maps finally became high enough quality,” Lyft’s chief product officer Dylan Lorimer says. “It was the perfect point in time.”

And Lyft had another valuable resource at its disposal: data from Lyft rides, which traverse the most highly trafficked streets multiple times every day. (According to Lorimer, between 70% and 80% of U.S. road segments host a Lyft ride at least once every ten days.) It launched a pilot in which a small subset of rides using car-mounted cameras collects the data so the company could update its maps with road closures, construction, or other obstacles.

Doing the impossible

By late 2019, Lorimer and Justin Moore, then the head of engineering, were ready to form a team to “do the impossible” — create a home-grown mapping system. A group of 250 — including the company’s first cartographers and a new mapping experiences team — got to work making the experience of the app smoother for drivers and passengers. “Google and Apple do a bunch of things really well,” says product manager Kieran Gupta. “But there’s a whole bunch of things they don’t do at all and that they are never going to do, and a subset of those are critical to drivers and riders on the Lyft platform.” For example, Google could navigate drivers to a destination but couldn’t tell them the most convenient place to drop off a rider or warn them about loading zones or bus stops or other complications. Ironically enough, the Google Maps developer tools didn’t work well with Android Auto or Apple’s CarPlay, which let drivers navigate via their car’s touchscreens rather than on their phones.

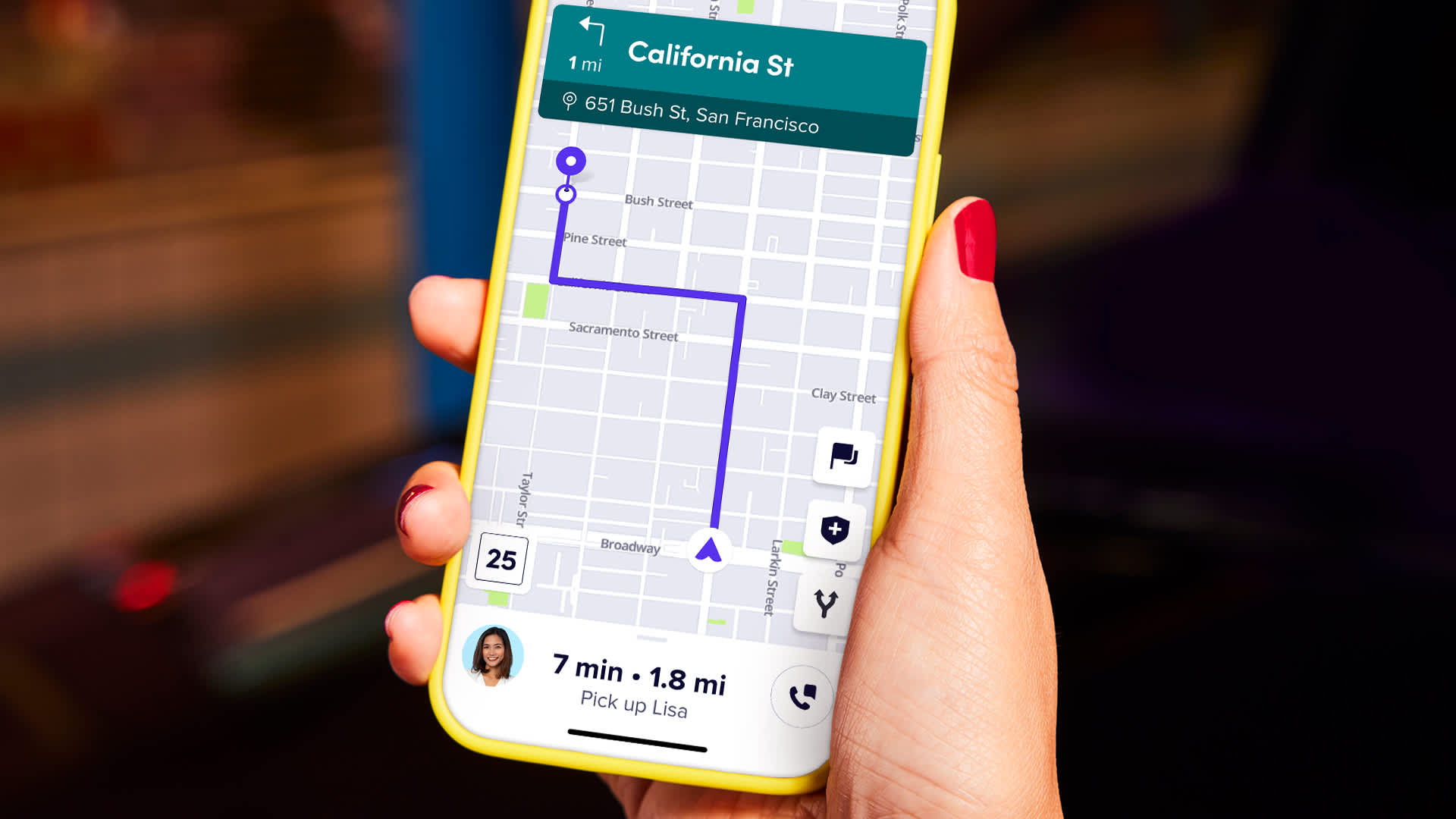

Lyft Maps reimagined the visual map, removing the distracting clutter of irrelevant stores, restaurants, and nearby destinations so that drivers could focus on the navigation and picking up passengers. They added a photo of the pickup area for drivers awaiting passengers, so they can better navigate unfamiliar streetscapes. They incorporated real-world updates, for example, alerting riders awaiting pickup if their driver is stuck in traffic. And, yes, they added CarPlay and Android Auto functionality.

So far, drivers seem to like it. Ninety-eight percent of drivers who try Lyft’s maps stick with them — rather than switching to Google, Apple, Waze, or any other app. “We never forced drivers to use our navigation,” Lorimer says. “We gave them a choice, and then we consistently sought their feedback to make it better and better to the point where they prefer it over the alternative.”

Now that the team has built a successful mapping product, they are starting to think about what other rideshare-specific features could set it apart — and improve the driving and riding experience. Some ideas they’ve been pursuing include a feature that lets drivers share information about accidents, traffic jams, passenger loading zones, and other rideshare frustrations; an option for riders to select a “scenic route,” rather than the most efficient; and pickup and drop-off guides to heavily trafficked destinations, so drivers and riders can get in and out of the airport (or stadium or park) more easily.

“There are so many micro-optimizations to improve these experiences that happen one million times a day,” says Gupta. “They may not seem like a big deal, but they could make the difference between a rider saying, ‘That was really stressful, and I’m going to give my driver a bad rating’ and ‘That was easy, and I’ll do it again.’ ”